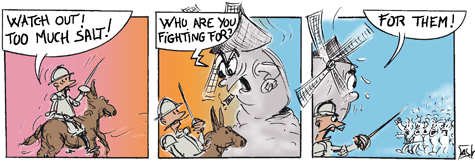

Why would a scientific researcher working in the public interest not seek to publicise results with important implications for public health? Pierre Meneton, a researcher at INSERM, the French Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, decided to draw attention to the cardiovascular risks associated with excessive salt consumption (1).

International guidelines on salt intake agree on the need to inform the public of the dangers of excessive salt consumption, and for information on salt content to be systematically provided on the labels of processed foods (1-4). Yet these recommendations are largely ignored in France (1).

Countering misleading information Pierre Meneton decided to denounce the “information” issued by the salt industry, and the ineffectual responses of the French authorities under the influence of food processing industry lobbyists, as well as the lack of necessary regulations such as systematic labelling of processed foods (1,5).

In 2007, Pierre Meneton was taken to court by the salt industry, via the Comité des Salines de France (Salt Producers’ Syndicate of France), who accused him of libel when he claimed (our translation): “Lobbyists for the salt and food processing industry are very active. They misinform healthcare professionals and the media” (6).

The right and obligation to blow the whistle Pierre Meneton, far from being intimidated, decided to use the trial to air his point of view. The court ruled in his favour, pointing out that lobbies simply defend their vested interests. The court also stressed that, as a researcher, Pierre Meneton had a right and even an obligation to challenge the salt lobby in good faith (a)(7). The court’s decision supports independent scientific analysis.

Others should follow this outspoken researcher’s example and be willing to argue their position without waiting for a law to protect whistle-blowers (8).

Pierre Meneton’s case illustrates that healthcare professionals and researchers alike can successfully fight misinformation and special interests, provided they base their arguments on solid scientific evidence and network with like-minded individuals.

©Prescrire 2008

Prescrire Int 2008; 17 (97): 217.

Notes:

a- Direct testimony: members of the Prescrire team attended the hearing.

References:

1 - Meneton P “La lutte contre l’excès de sel alimentaire” Rev Prescrire 2004; 24 (248): 232-233.

2 - Prescrire Editorial Staff “Adult hypertension : reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality” Prescrire Int 2005; 14 (75): 25-33.

3 - Prescrire Rédaction “Alimentation des enfants : des salières sur la table de la cantine scolaire?” Rev Prescrire 2005; 25 (259): 236.

4 - Prescrire Rédaction “Sel et évènements cardiovasculaires” Rev Prescrire 2007; 27 (290): 927.

5 - Cattan P “Scandale alimentaire. Sel: le vice caché” TOC du 18 March 2006: 14-15.

6 - AFP “Les méfaits du sel sur la santé au centre d’un procès en diffamation“ Release 31 January 2008: 1 page.

7 - AFP “Les producteurs de sel perdent leur procès contre un chercheur de l’Inserm” Release 13 March 2008: 1 page.

8 - AFP “Des scientifiques demandent la protection des “lanceurs d’alerte”” Release 29 January 2008: 1 page.